The USF College of Arts and Sciences (CAS) conservation biology program aims to train the next generation of scientists who will address critical issues in biodiversity conservation.

Net used to collect bat feces. (Photo courtesy of Emily Birdsall)

“We recognized that there was a critical local, state and regional need for biologists with training and research experience in conservation to protect and manage our native species, communities, and ecosystems, and we created this graduate program in 2017 to address this shortage,” said Dr. Melanie Riedinger-Whitmore, St. Petersburg campus chair for the Department of Integrative Biology.

The thesis-based Master of Science program introduces students to the critical areas impacting biodiversity (habitat degradation, climate change, invasive species, pollution and over-exploitation), and provides them with the skill sets and knowledge needed for careers and research in wildlife and natural resource management and ecological restoration.

Conservation biology graduate students conduct both applied and basic research, and most students have research projects aligned with faculty research. Many students also work closely with non-profit or government agencies, and these connections help them establish important professional partnerships.

Finding a non-invasive way to collect DNA from endangered species

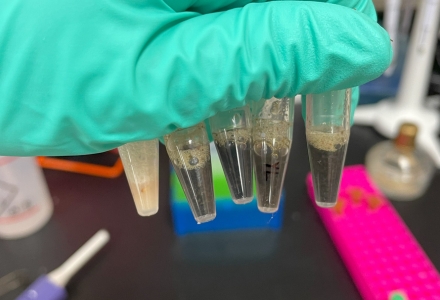

Conducting analysis of the samples. (Photo courtesy of Emily Birdsall)

Emily Birdsall decided to earn her master’s in conservation biology because “I love science and I want to work in a field where I can make a difference in the preservation of natural areas.”

She’s just completed the lab portion of her research and is currently in the analysis phase to develop a non-invasive approach to acquiring genetic material from endangered species.

She collected fecal pellets from the Florida Bonneted Bat to isolate and amplify microsatellite markers, which can be used for population-wide analyses.

“I am amplifying mitochondrial DNA to accompany the microsatellite data, which can also be used in studies of maternal lineages. I am also amplifying 16S and 18S ribosomal RNA from each pellet, which I will send to a facility for metagenomic sequencing,” she said. “The 16S data will give me an idea of the bacterial species present within the sample which can be used to construct a baseline dataset of the gut microbiome. The 18S data will be used to identify prey species (insects) present within the sample, which can be used for a diet analysis.”

Her samples were collected from two sites in Miami-Dade County in collaboration with Bat Conservation International and Zoo Miami. She’s also conducting lab work at USF St. Petersburg Department of Integrative Biology faculty Dr. Deby Cassill, Dr. Michelle Green, and Dr. Mike Shamblott.

“This area of research is important to me because it provides an additional method of sample collection that greatly reduces stress to the animals, as well as increasing the genetic work that can be done,” Birdsall said. “Permitting to work with federally listed species is often lengthy and difficult, however the endangered species act does not extend to feces making the process much more realistic. This should matter to the public because bats are critical species within ecosystems across the globe. They provide insect suppression services which reduces the need for pesticides, as well as helping to pollinate plants and distribute seeds across great distances.”

Bats, Birdsall explained, are almost exclusively responsible for the pollination of agave plants, and this research helps to expand bat studies which in turn will further conservation actions.

“My work is not yet completed, but so far, I have found that DNA isolation from bat feces is possible, although there have been various setbacks such as small samples size and low DNA yield,” she said. “These findings have not surprised me however, as these issues are typical for fecal work as well as bat samples.”

Birdsall said she hopes that her research makes sample acquisition and genetic analysis easier and more accessible to a wider range of people.

“In the long run, this will increase the proportion of animal species that can be studied and consequently conserved,” she said. “My favorite part of this experience has been the people that I have had the privilege to work with. I have learned so much from my advisors and know that their mentorship will serve me as I continue my education and enter the workforce.”

Birdsall is on track to graduate this fall semester and hopes to work in field biology or molecular biology. She also plans to return to earn her PhD.

Impact of warming temperatures for frog tadpoles

Jessalyn Aretz has always loved animals, with a special affinity for “creepy-crawlies.”

She said her interest in this field started when she worked in Dr. Stephan Deban's lab at the Tampa campus as an undergraduate, studying salamander biomechanics.

A native tree frog. (Photo courtesy of Jessalyn Aretz)

Native tree frog tadpole. (Photo courtesy of Jessalyn Aretz)

“During that time, I completely fell in love with how unique and charismatic amphibians are. A lot of people don't know much about them, and worse: amphibians are disproportionately threatened by things like habitat destruction and pollution,” she said. “When I learned about this degree program at St. Pete, it really clicked that I wanted to keep learning about these little guys and how I could help them, especially in a place like Florida, which is so beautiful but also more urbanized every day.”

Aretz is looking at the impact of warming temperatures, in the form of urban heat and climate warming, on the thermal ecology and swimming preference of a native tree frog tadpole, Dryophytes femoralis.

“In amphibian species, temperature can impact traits such as locomotor performance, breeding times, and even dietary preferences. However, the exact impacts can depend on the species being studied as well as factors like where the study population is located or the conditions that a particular individual was exposed to during its development,” she said. “The pinewoods tree frog is particularly interesting because while this species has been shown to be urban-sensitive, not much is known about its thermal ecology and many people haven't even heard of it.“

As a student in Dr. Alison Gainsbury’s lab on the St. Pete campus, Aretz is currently conducting research this summer at the USF Forest Preserve, Lower Hillsborough Preserve, and Archbold biological station to collect frog eggs and tadpoles.

She is bringing the eggs and tadpoles back to the lab to run tests on maximum and minimum temperature tolerances, thermal preferences, growth rates, and swimming speeds across different temperatures.

“I do have some preliminary data from last summer that already suggests that tadpoles from different populations/localities exhibit different thermal thresholds and tolerances, so I'm very interested to explore why that might be happening with my field work this summer,” she said.

Aretz says the health of the amphibian population in an ecosystem is a good indicator of the health of the rest of the habitat.

“Amphibians are an incredibly important part of their ecosystems. They're important as both predators and prey, help control pest insect populations, and serve as ecosystem health indicators because they're so sensitive to chemical contaminants and other environmental changes,” she said. “If we understand how urbanization and changing climates might be impacting local amphibian populations and how they deal with temperature increases and fluctuations, we can come up with management plans focused on protecting them and the habitat they live in, like green urban spaces, wildlife corridors, preserving wetlands, etc.”

She hopes her research will contribute to the growing body of knowledge about how species and populations are currently being affected by growing urban sprawl and “human-driven climate warming.”

“If we can anticipate how they'll respond, we can put together mitigation strategies that protect vulnerable or threatened communities before it's too late. Also, the tropics and subtropics are the most biodiverse and productive places on the planet and also some of the most threatened by humans, but they're relatively understudied compared to temperate places. The more we can the learn about tropical species and ecosystems, the better equipped we are to protect them in a future that's getting warmer and warmer.”

Aretz says the CAS conservation biology master’s program has allowed her to meet and learn from so many inspiring people.

“I have absolutely loved getting to know my fellow grad students, who are just as passionate about protecting our forests, oceans, wetlands; also, the field work is really fun! I get to go tromp around in the woods for hours and work hands on with Florida's beautiful and unique ecosystems,” she added.

She plans to graduate this upcoming fall semester and pursue a career dedicated to amphibian conservation.

“If you're passionate about conservation and teaching people to care about the world around them, then this is an incredibly fulfilling experience,” Aretz said. “The professors and other students here are absolutely amazing and I've learned so much. It's a lot of work, but it's been worth it. Also, we always need more people willing to advocate for the creatures that can't speak for themselves.”

Learn more about applying to the CAS conservation biology master’s degree program.