In August 2021, Dr. John Parkinson, an assistant professor in the USF College of Arts and Sciences Department of Integrative Biology, was awarded a National Science Foundation (NSF) grant to help coordinate and fund a workshop that brought together more than 60 scientists from 12 countries to build consensus around the assessment and interpretation of coral symbiont diversity. Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, the workshop was held virtually.

Now, the results of that workshop have been released in the form of an 80-page manuscript and an NSF white paper that highlight consensus assessments and interpretations. These guidelines will help scientists better coordinate their research efforts, furthering the ultimate goal of protecting and regenerating coral reefs that are under threat around the world.

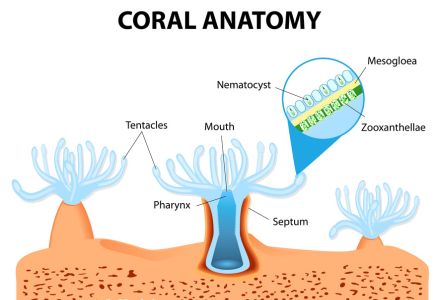

Illustration showing coral anatomy, including zooxanthellae. (Photo source: Adobe Stock)

Coral symbionts (known formally as Symbiodiniaceae and colloquially as ‘zooxanthellae’) belong to a family of marine micro-algae notable for their mutualistic associations with reef-building corals, sea anemones, jellyfish, sponges and other marine invertebrates.

Parkinson fell into coral research as an undergraduate at the University of Miami. While training in scuba diving, he learned about coral bleaching and the global decline of reef ecosystems.

“I wanted to help,” Parkinson said. “I also had an itch to work with DNA thanks to a long-time obsession with the film Jurassic Park. Symbiodiniaceae diversity research checked all the boxes.”

“Historically, this field has been contentious,” Parkinson explained. “There are many ways to interpret complex symbiont molecular data, so in the past, we’ve butt heads over which approaches are best. For the recommendations coming out of the workshop to carry any weight, it was important that all the different viewpoints be represented and discussed.”

“I am happy to report that we agreed far more often than we disagreed on most matters,” Parkinson continued. “Some key outcomes included general acceptance of the new Symbiodiniaceae species and genus names; recognition that resolving species is important for many—but not all—research questions; and acknowledgment that the most commonly used DNA markers have many technical issues, so additional markers should be developed.”

Parkinson admits there is still work to be done.

One area where there is still some disagreement relates to the DNA marker ITS2–a popular phylogenetic marker that is often considered a universal DNA “barcode.” Parkinson says aspects of how ITS2 is used for these particular organisms can cause confusion.

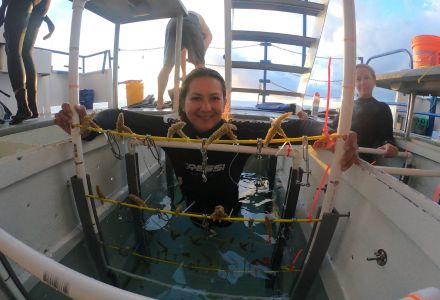

Preparing coral fragments for transport in the live-well of Shedd Aquarium’s research vessel, the Coral Reef II. (Photo courtesy of Liv Williamson)

A colony of brain coral. (Photo courtesy of Liv Williamson)

“It can be hard to tell if different ITS2 sequences represent different symbiont species, and the relative abundance of sequences doesn’t necessarily reflect the number of symbiont cells in a coral colony,” he explained.

“Many disagreements over coral symbiont community diversity come down to these two problems. To address them, we will need to use algal cultures in the laboratory to create mock mixtures of symbionts, where we know the exact diversity and abundance of each species, then sequence ITS2 (along with other markers) to figure out which of our analytical approaches most closely recovers the true diversity and abundance,” Parkinson continued. “Only then, do I think we’d be able to agree on which approach is best.”

The experiments being conducted in Parkinson’s lab at USF, which has one of the most diverse symbiont culture collections in the country, seek to address some of these areas.

“In addition to moving forward with mock cultures, my lab is heavily involved in sequencing new Symbiodiniaceae genomes and expanding molecular resources—another area identified as a priority during the workshop,” he said. “We are also trying to build a key to facilitate choosing which series of markers and methods will help you identify the symbionts in your coral sample to the species level as quickly and inexpensively as possible.”

He hopes to continue that research and collect data that can be presented to the scientific community in the future to build on the consensus findings.

Parkinson is also hopeful that in the next five to 10 years advancements will be made in the field of genomics.

Measuring new coral fragments in the nursery to begin tracking their growth over time. (Photo courtesy of Liv Williamson)

“We should be able to greatly increase the number of species with sequenced genomes, from around a dozen today to over 100 in the next few years, and use that data to explore how these organisms evolve and diversify,” he said. “We should also be able to expand the number of species maintained in culture, which will allow for more experiments to better understand physiological diversity among coral symbionts.”

“On the community level, my main hope is that these recommendations reach a broad audience and that more people jump into our field,” he continued. “Hopefully the fact that we were able to reach consensus on a large range of topics will encourage a growing membership.”

Parkinson understands the implications of complacency or regression in these research areas have dire consequences.

“The climate crisis facing corals and their symbionts is existential and we need new people and new ideas to innovate solutions,” he said. “As a research community, we need to be more inclusive and supportive than we have been in the past and encourage more equitable collaboration between scientists from different countries.”

The NSF grant funded the three organizers as well as three graduate students, who were intimately involved in planning and executing the workshop, a professional facilitator to ensure the virtual meeting ran smoothly, and the ability to publish the findings in an open-access journal, which means anyone can read it for free. If you are interested in reading the report, it is available on PeerJ Hubs on behalf of The International Association for Biological Oceanography.