AGU press contact:

Lauren Lipuma

+1 (202) 777-7396 (GMT-4)

Contact information for the researchers:

Chuanmin Hu, University of South Florida (GMT-4)

+1 (727) 553-3987

Lin Qi, Xiamen University, China (GMT+8)

Sheng-Fang Tsai, National Taiwan Ocean University (GMT+8)

WASHINGTON – Scientists have, for the first time, used satellites to track the bioluminescent

plankton responsible for producing “blue tears” in China’s coastal waters and found

the sparkly creatures have become more abundant in recent years.

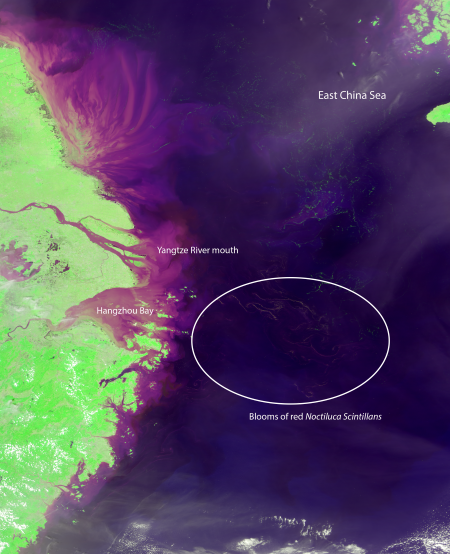

A satellite image of the East China Sea, taken by NASA’s MODIS instrument, showing blooms of red Noctiluca scintillans east of Hangzhou Bay. Credit: NASA/University of South Florida optical oceanography lab.

Red Noctiluca scintillans are single-celled organisms found in coastal waters all

over the world. Commonly known as sea sparkles, at night the organisms glow a bright

blue when disturbed by swimmers, waves or passing boats. The sea sparkles’ dazzling

blue light, often called “blue tears,” can be seen after dark on many of China’s shores

and have become a major tourist attraction in recent years, especially in Taiwan’s

Matsu Islands.

Blooms of Noctiluca scintillans are one form of red tides that can harm marine life, but scientists have difficulty monitoring these outbreaks. Researchers typically study the blooms by taking measurements from ships, but these measurements don’t show how the blooms are distributed over a large area of ocean or how they change over time.

Scientists report in a new study in AGU’s journal Geophysical Research Letters they have developed a way to track red Noctiluca scintillans blooms by satellite using the organism’s unique ability to absorb and scatter light.

The researchers used their new method to track red Noctiluca scintillans blooms in the East China Sea from 2000 to 2017. They found the twinkly creatures can survive farther from shore and in warmer waters than previously thought.

Their results also show red Noctiluca scintillans blooms have become more frequent in recent years and the organism’s abundance could have been affected by construction of the controversial Three Gorges Dam in the early 2000s.

The new method will help researchers build a more complete picture of red Noctiluca scintillans blooms in this area, according to Lin Qi, an optical oceanographer at Sun Yat-Sen University in China and lead author of the new study.

Blue bioluminescence produced by red Noctiluca scintillans when a drop of water is introduced into an aquarium. Credit: Sheng-Fang Tsai, National Taiwan Ocean University

The new method could also help researchers better track harmful red tides and boost

tourism on China’s east coast, according to Sheng-Fang Tsai, a marine ecologist at

the National Taiwan Ocean University and co-author of the new study. If researchers

have a better idea of when and where red Noctiluca scintillans blooms occur, local

officials could potentially use the information to inform tourists when they have

the best chance of seeing the glittering blue tears.

Measuring color from space

Researchers from Belgium discovered in the mid-2000s that red Noctiluca scintillans are unique when it comes to absorbing and scattering light. Their bodies absorb more blue light and scatter more red light than other ocean microorganisms, so researchers thought they could identify them by analyzing changes to the ocean’s color.

In the new study, researchers tried to pick out the unique colors of red Noctiluca scintillans blooms from satellite images. They analyzed nearly 1,000 images of the East China Sea taken by instruments on NASA’s Terra and Aqua satellites and the International Space Station from 2000 to 2017.

Their method worked – the researchers were able to identify many red Noctiluca scintillans blooms in the East China Sea from April to August over the 18-year period. The blooms typically show up close to shore, often near river mouths or deltas. But, interestingly, the new study found many blooms located farther from the coast than previously observed by ships – some blooms were more than 300 kilometers (180 miles) offshore.

The researchers also identified blooms residing in waters outside of the species’ usual temperature range. Previous research found red Noctiluca scintillans normally reside in waters around 20 to 25 degrees Celsius (68 to 77 degrees Fahrenheit), but the new study found them in waters as warm as 28 degrees Celsius (82 degrees Fahrenheit).

Scientists report in a new study they have found a way for satellites to track the bioluminescent plankton responsible for producing “blue tears” in China’s coastal waters and found the sparkly creatures have become more abundant in recent years. Red Noctiluca scintillans are single-celled organisms found in coastal waters all over the world. Commonly known as sea sparkles, at night the organisms glow a bright blue when disturbed by swimmers, waves or passing boats. The sea sparkles’ dazzling blue light, often called “blue tears,” can be seen after dark on many of China’s shores and have become a major tourist attraction in recent years, especially in Taiwan’s Matsu Islands. Scientists report in AGU’s journal Geophysical Research Letters they have developed a way to track red Noctiluca scintillans blooms by satellite using the organism’s unique ability to absorb and scatter light. The new method will help researchers build a more complete picture of red Noctiluca scintillans blooms in this area, could help researchers better track harmful red tides, and could boost tourism on China’s east coast. If researchers have a better idea of when and where red Noctiluca scintillans blooms occur, local officials could potentially use the information to inform tourists when they have the best chance of seeing the glittering blue tears on a given night.

The size and duration of the blooms varied from year to year, but the researchers saw the blooms were increasing in recent years, especially between 2013 and 2017. In 2017, they even saw a prolonged bloom that lasted from mid-April to mid-July. They need more yearly observations to confirm their result, but the researchers suspect this to be an increasing trend.

Connection to Three Gorges Dam

The study authors suspect construction of China’s Three Gorges Dam could have been responsible for a decrease in red Noctiluca scintillans blooms in the early 2000s. The dam spans the Yangtze River in eastern China and generates roughly the amount of energy as 12 nuclear reactors. The dam has been controversial since Chinese leaders first proposed it because of its impacts on the environment and its displacement of more than a million local residents.

Individual cells of red Noctiluca scintillans seen glowing blue under a microscope. The organism’s balloon-shaped bodies give them the buoyancy to float on the sea surface where humans can observe them. Credit: Sheng-Fang Tsai, National Taiwan Ocean University

Construction on the dam began in 1994 and was completed in 2006; the dam became fully

operational in 2012. Water flow on the Yangtze River dramatically decreased during

construction, but once the dam was filled and became operational, the flow rebounded.

The Yangtze River empties into the East China Sea and red Noctiluca scintillans blooms

are often found near the river’s mouth, so the authors suspect the reduced river flow

during the dam’s construction reduced red Noctiluca scintillans blooms from 2000 to

2003.

The researchers suspect the increase in red Noctiluca scintillans from 2013 to 2017 could be a result of excess nutrients entering the East China from increased fertilizer use, among other factors. If this is true, the trend may continue in the coming years, according to the authors.

Founded in 1919, AGU is a not-for-profit scientific society dedicated to advancing Earth and space science

for the benefit of humanity. We support 60,000 members, who reside in 135 countries,

as well as our broader community, through high-quality scholarly publications, dynamic

meetings, our dedication to science policy and science communications, and our commitment

to building a diverse and inclusive workforce, as well as many other innovative programs. AGU

is home to the award-winning news publication Eos, the Thriving Earth Exchange, where scientists and community leaders work together to tackle local issues, and

a headquarters building that represents Washington, D.C.’s first net zero energy commercial renovation. We

are celebrating our Centennial in 2019. #AGU100

Read more about this research on AGU’s Newsroom:

https://news.agu.org/press-release/chinas-sparkling-bioluminescent-seas-are-glowing-brighter/

Read the new study about this research here:

https://agupubs.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1029/2019GL082667/

Imagery provided by:

Google Earth

Yu-Xian Yang, Lienchiang county government, Taiwan

Sheng-Fang Tsai, National Taiwan Ocean University

Chuanmin Hu, University of South Florida Optical Oceanography Lab/NASA:

https://optics.marine.usf.edu/subscription/modis/ECS/2017/daily/138/A20171380515.QKM.ECS.PASS.L3D.FRGB.png

NASA:

https://earthobservatory.nasa.gov/images/92622/midsummer-sunrise-gulf-of-saint-lawrence

Mutolisp, album “Matsu” on Flickr: https://www.flickr.com/photos/mutolisp/albums/72157629866398063/with/6975437064/, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0: https://www.flickr.com/people/mutolisp/

Lucas Bento, CC BY SA 4.0:

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Planctons_bioluminescents_(Noctiluca_scintillans).jpg

Bruce Anderson, CC BY 2.0:

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Blue_Tide-_Noctiluca.jpeg

Franz Krachtus, CC BY:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NjWTr_cXqNs

Tom Fisk:

https://www.pexels.com/video/aerial-view-of-the-sea-and-a-beautiful-island-1550083/

Music:

Waves Of Tranquility by spinningmerkaba, CC BY 3.0:

http://dig.ccmixter.org/files/jlbrock44/59736

Video produced by Lauren Lipuma at AGU.