By: Dyllan Furness, Director of Communications

As Florida braced for Hurricane Helene in September, an underwater glider operated by the USF College of Marine Science (CMS) was in a unique and precarious position — it was the only submersible research vessel in the direct path of the storm.

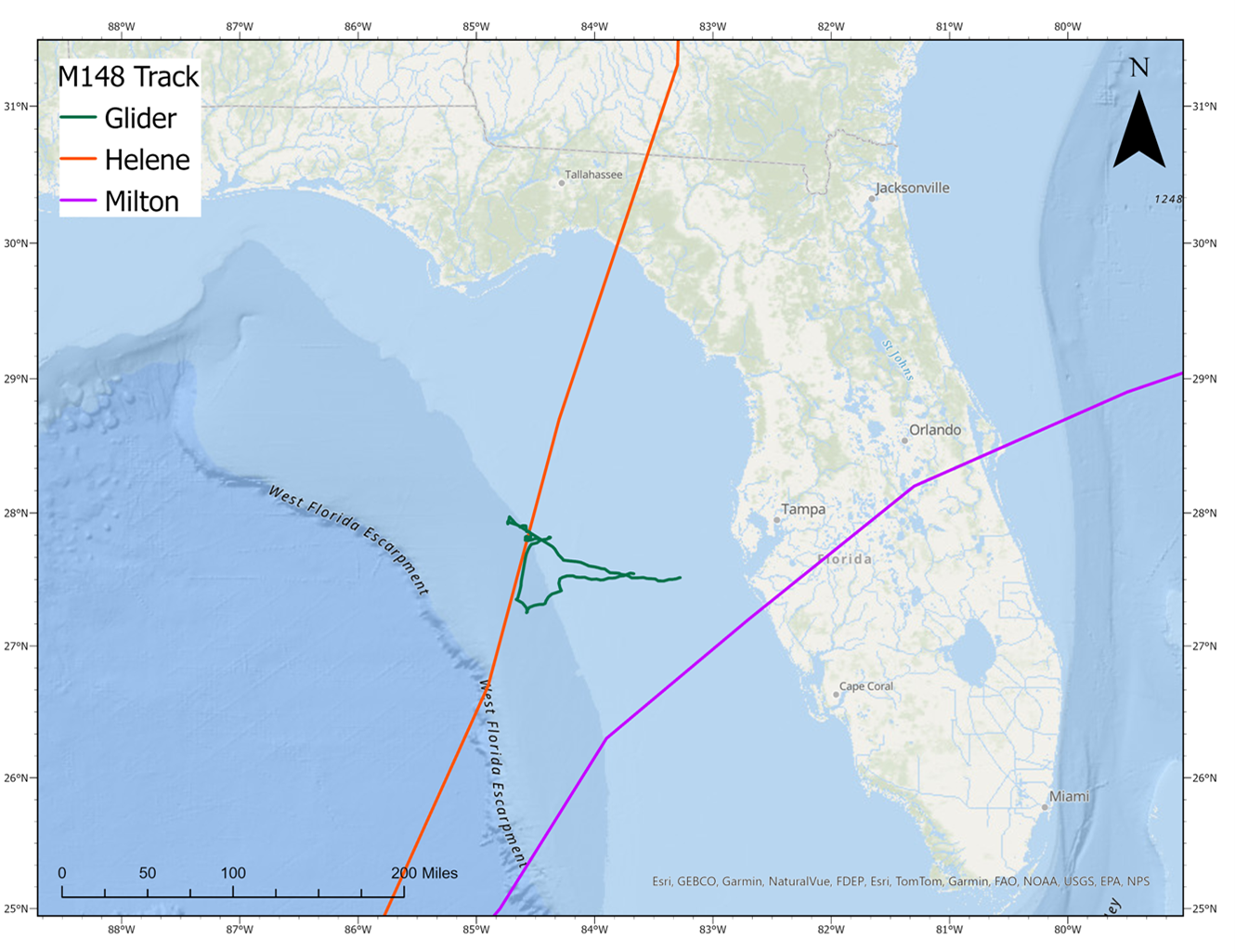

Deployed by the Ocean Technology Group to monitor red tide, the glider, nicknamed Jai Alai, was carefully stationed at the edge of the West Florida Shelf at a location that ended up being directly in the path of the hurricane.

“We were cautious about putting the glider in the line of fire,” said Chad Lembke, a research faculty member and project engineer at CMS. “Helene was a good-sized storm. We didn’t want to lose our equipment.”

Gliders are remotely operated submersibles that capture and transmit data from the water column for weeks to months at a time. Data such as temperature and salinity gathered by gliders are fed into oceanographic and weather models, allowing forecasters to better predict the paths and intensities of storms before they make landfall.

Warm water fuels hurricanes, so determining the ocean’s heat content is key for forecasting a storm’s ability to strengthen. Not only have gliders and other uncrewed research vessels proven effective at gathering these data, but they are also safer than sending people on boats into the path of a hurricane.

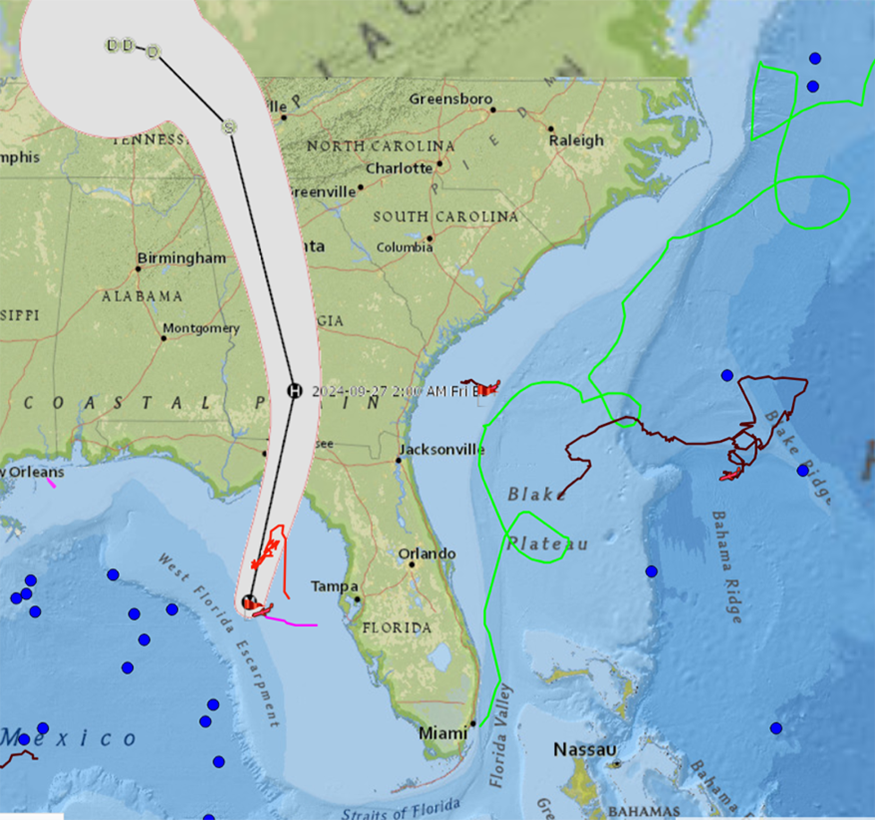

Last year, CMS received several grants from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) to gather ocean data in the eastern Gulf of Mexico and along the South Atlantic Bight, which stretches from North Carolina to the Florida Keys. These efforts support research related to red tide, fisheries, and hurricanes.

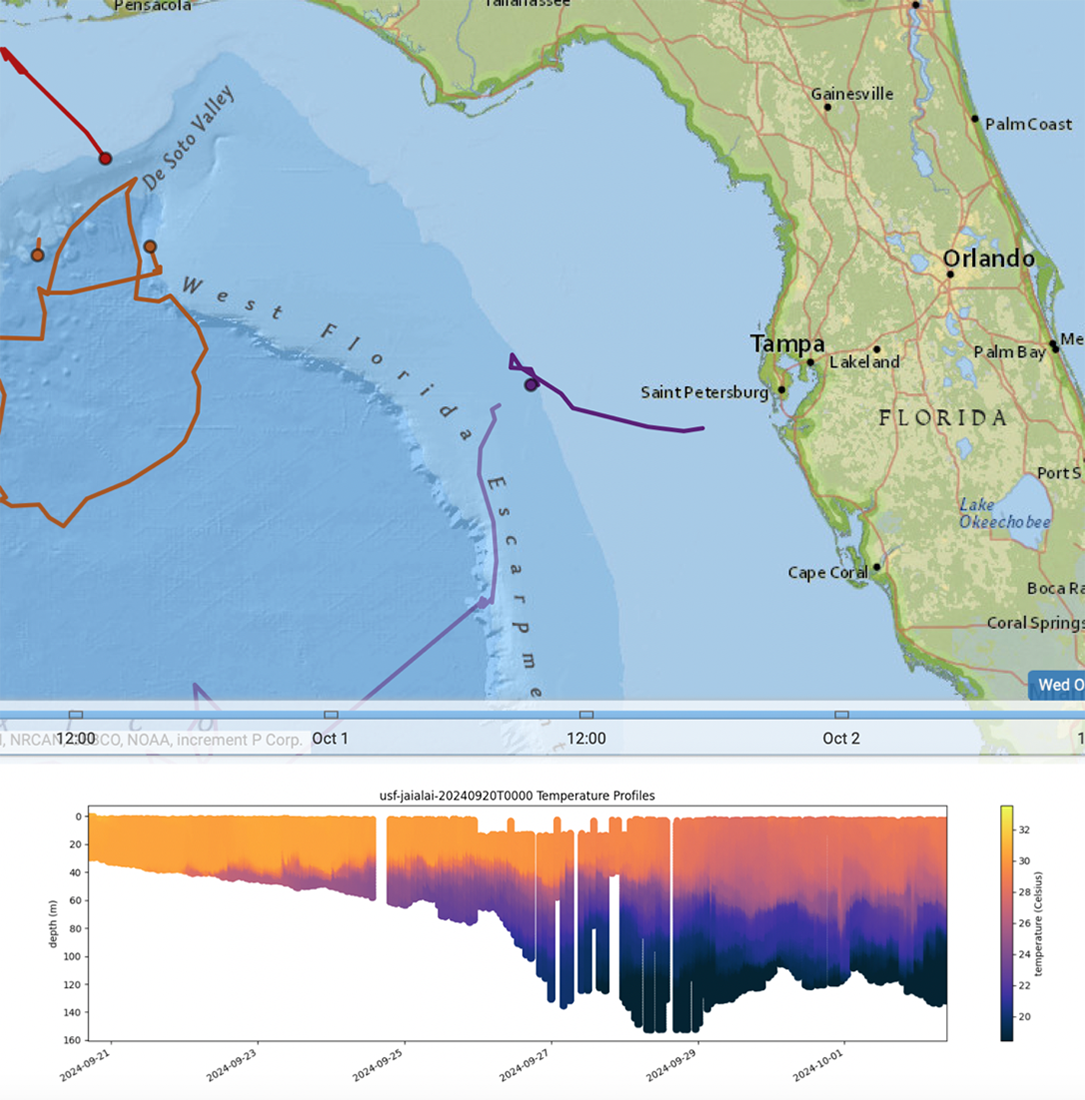

Gliders fill a gap in the data between the sea surface and seafloor, Lembke said, and help forecasters “tighten up” weather models thanks to the data they provide from the water column. In the days before Helene’s landfall, Jai Alai detected a deep reservoir of warm water in the storm’s projected path, giving it an abundance of fuel to intensify rapidly. Supercharged by this warm water, Helene grew from a tropical storm to a major Category 4 hurricane in just two days.

IMAGE ABOVE: Water column temperature collected by Jai Alai before Helene showed a deep layer of warm water, which fueled the intensity of the hurricanes.

To keep Jai Alai safe as Helene passed overhead, the Ocean Technology Group instructed the glider to work around the middle of the water column, safe from Helene’s massive waves at the surface and the powerful forces of circulation near the seafloor.

The glider was instructed to minimize its time communicating while the storm passed. It resurfaced and transmitted a signal around 10pm on Thursday, September 26. The signal came as a huge relief to the glider team.

“Things were beginning to get rough around St. Pete, but we were closely watching the glider,” he said. “We were happy to see it made it through the storm.”

Lembke and his collaborators see Helene as a case in point for the value of gliders and other oceanographic observations, and envision a network of these research instruments across hurricane hotspots such as the Gulf of Mexico, the Caribbean, and Atlantic coast.

IMAGE ABOVE: Jai Alai was in the direct path of hurricane Helene, collecting data on water temperature, salinity before it made landfall in northern Florida.

Leading this effort on a national scale is NOAA’s U.S. Integrated Ocean Observing System (IOOS), while the Gulf of Mexico Ocean Observing System (GCOOS) coordinates efforts across the Guld of Mexico, including the work of the Ocean Technology Group.

“Gliders are not only the most cost-effective technology available to collect ocean condition data for up to four months, but also a safe option for the researchers in our network,” said Jorge Brenner, executive director of GCOOS. “It would be practically impossible for anyone to collect the complex tridimensional ocean data needed by the National Weather Service across the water column during a storm such as Hurricane Helene. But for Jai Alai that was possible.”

As ocean temperatures continue to rise and fuel hurricanes, gliders and other uncrewed research vessels may prove to be indispensable tools for helping understand how the ocean can impact our lives.