By: Carlyn Scott, Science Communications Manager

A brown alga called Sargassum has inundated beaches in the Caribbean since 2011, impacting tourism, harming the health of humans and marine life, and costing local governments millions of dollars per year to clean up.

Scientists have been divided on the causes of the phenomenon known as the Great Atlantic Sargassum Belt (GASB). But a new study published in Nature Communications may have identified what drove a tipping point that established this alga in the tropical Atlantic Ocean.

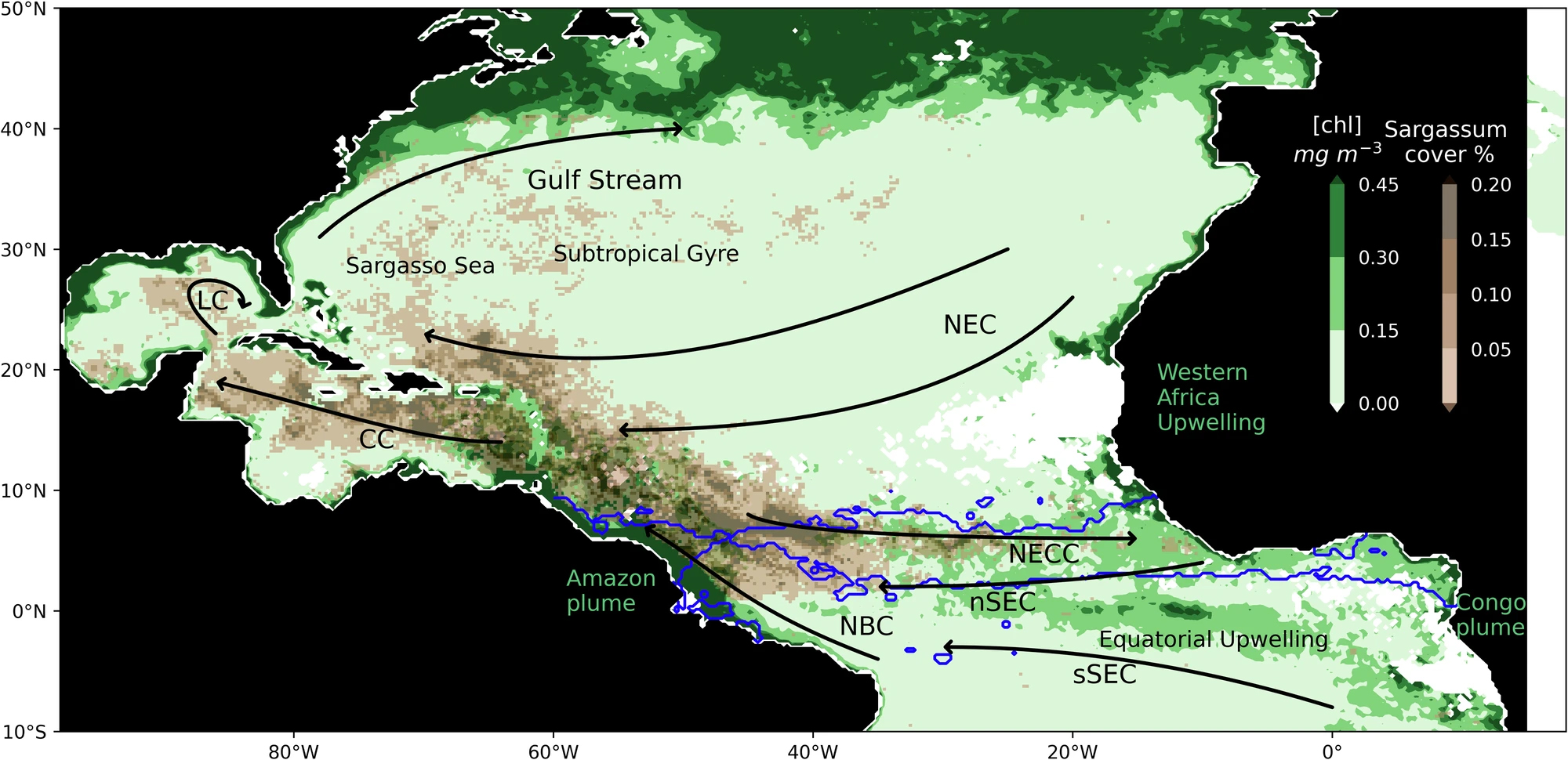

The key drivers were wind, ocean currents, and nutrients, according to the international team of researchers who published the recent study. Specifically, two consecutive years of a strong negative North Atlantic Oscillation (NAO), a shift in atmospheric pressure over the Atlantic that changes circulation and wind patterns, pushed Sargassum into the tropics. There it found warm, nutrient-rich waters, and lots of sunlight, all year-round.

“At first, the evidence is that just a few patches of Sargassum were being pushed south by winds and currents during this NAO period of 2009-2010,” said co-author Frank Muller-Karger, Distinguished University Professor and biological oceanographer at the USF College of Marine Science (CMS). “But these algae patches met the right conditions to grow and perpetuate blooms when they reached the area close to the equator.”

Every year, patches of Sargassum come together in the tropical Atlantic, pushed by the Trade Winds into an area where the ocean is rich in nutrients brought up from deeper waters below, explains Muller-Karger. These Sargassum patches form a new, large population in the region that spans from Africa to the Americas.

Authors of the recent paper in Nature Communications use a computer model that helped them to go into more details and test new scenarios than was possible in a prior study published in Progress in Oceanography. That study first identified the possible influence of the NAO on the dispersal of Sargassum. In both papers, researchers used models to simulate the transport of Sargassum from the northern to the southern part of the North Atlantic, testing if the NAO was the root cause of the first bloom that occurred in the tropical Atlantic in 2011.

“Both models showed that some patches of the Sargassum were swept up by the wind and currents from the Sargasso Sea toward Europe, then moved southward, and from there were injected into the tropical Atlantic. There, this population of algae, now separated from the Sargasso Sea, forms new blooms every year thanks to having enough light, nutrients, and warmer temperatures,” said Muller-Karger.

IMAGE ABOVE: Multiple MODIS satellite images were aggregated to show the typical annual Sargassum coverage and chlorophyll distribution after 2011. Sargassum was moved from the Sargasso Sea to the tropics via currents depicted by arrows. Figure from Jouanno et al. (2025).

These patches enriched with nutrients were identified as a driver of the GASB in a 2023 paper published in Nature Communications and co-authored by Chuanmin Hu, professor of physical oceanography at CMS.

Still, the question remained: What provided the nutrients to promote the growth of Sargassum in the tropical Atlantic?

Popular hypotheses included rivers such as the Amazon, Orinoco, Niger, Congo, the Mississippi, or even iron-rich dust from the Sahara Desert. But researchers lacked sufficient data to support any of these theories.

To determine nutrient sources, the group of international researchers again turned to computer models to analyze decades-worth of wind, currents, and three-dimensional nutrient measurements collected in the Atlantic Ocean. These models successfully reproduced the annual blooms.

The model showed that nutrients were supplied via an ocean process known as vertical mixing, in which water masses mix on a seasonal basis due to shifting winds, bringing deeper water that has higher nutrient concentrations to the surface. In this sunlit surface layer photosynthesis occurs and Sargassum grows. This vertical mixing of waters in the tropical Atlantic fuels the massive blooms that eventually ends up on the beaches of the Caribbean Sea and Gulf Coast.

VIDEO ABOVE: A time lapse model depicting interannual Sargassum blooms in the North Atlantic. The alga was pushed southward and injected into the tropics, where it proliferates today, through a series of currents. Video from Jouanno et al. (2025).

“This was a surprising result,” said Muller-Karger. “We had posed the hypothesis before that it is not the rivers that feed the formation of the Sargassum blooms in the tropical Atlantic. This model supports that nutrients from slightly deeper layers in the ocean feed the blooms.”

Despite the recent and largely negative press Sargassum has received, the seaweed is not new to the Atlantic. Sailors in the 15th century first recorded this Sargassum in the western North Atlantic, which they named the Sargasso Sea. However, the large-scale recurring blooms of Sargassum that flow into the Caribbean every year are a new phenomenon.

Julien Jouanno, lead author of the study and physical oceanographer at the University of Toulouse, emphasized the complex changes in the circulation of the atmosphere and the ocean that led to the transport of Sargassum from the Sargasso Sea to the tropical Atlantic.

“At this stage, we cannot say for certain whether this abnormal event is a direct result of climate change,” said Jouanno. “There are many moving parts in a computer simulation, and we may still not have good representation of the factors that control Sargassum growth and mortality.”

Indeed, there are unanswered questions regarding the biology and ecology of Sargassum, and the species present within the GASB remains a mystery. Researchers hope that by investigating the physiology and biology of Sargassum in the Sargasso Sea, they can understand how it might react to environmental changes.

Still, the authors remain hopeful that collaborative efforts can help advance the study of Sargassum.

“This analysis and the publication highlight the importance of international cooperation in studying and dealing with the ‘Sargassum problem’ in the Atlantic,” said Julio Sheinbaum, a physical oceanographer from Center for Scientific Research and Higher Education (CICESE) at Ensenada, Mexico.

This publication was an international collaboration between University of Toulouse, the Center for Scientific Research and Higher Education CICESE, Sorbonne University, and the University of South Florida.