By Paul Guzzo, University Communications and Marketing

In the 1980s, a visionary professor of computer science and engineering at the University of South Florida joined forces with his ambitious doctoral student to explore a technology that was still in its infancy.

They taught an artificial intelligence system to identify a chair.

Renderings used to train AI on how to identify chairs [Courtesy of Louise Stark]

Arnie Bellini announced an historic $40 gift to name the Bellini College of Artificial Intelligence, Cybersecurity and Computing

Today, such work may seem rudimentary. However, at that time, it was groundbreaking for global artificial intelligence research and for USF.

USF continues to lead in AI. In the fall, it will launch the Bellini College of Artificial Intelligence, Cybersecurity and Computing, the first of its kind in Florida, and one of the few like it in the country. It’s also the first named college dedicated to the fields thanks to an historic $40 million gift from Arnie and Lauren Bellini.

“It’s a huge step for the university,” said Louise Stark, the USF alumna who worked on the chair project. “Congratulations to USF.”

This step is part of a much larger journey that began four decades ago with a group of pioneering professors and students who specialized in artificial intelligence when the field was seeking public acceptance and support.

“AI wasn’t a national conversation back then,” said Lawrence Hall, who’s been researching artificial intelligence since he joined USF in 1986 and serves as co-director of the USF Institute for Artificial Intelligence + X. “There wasn’t really any conversation about it outside of those who were doing the work.”

Kevin Bowyer, former USF professor

Those pioneers had to start the conversation.

Hall dates USF’s artificial intelligence research to 1984 with the arrival of Kevin Bowyer, the professor who worked on that chair project.

Perhaps that is accurate, Bowyer said, but he was not certain that someone did not come before him.

“I can definitively say that there weren’t many of us back then,” said Bowyer, now a professor with the University of Notre Dame’s Department of Computer Science and Engineering. “We were determined to build USF’s AI research block by block, piece by piece, and we had big aspirations.”

But the same pioneers had very little technology to support those ambitions.

“There was no Amazon,” Bowyer said with a laugh. “Computer science artifacts were much more expensive back then, so if you wanted something like a 3D scanner, it wasn’t something you could easily get. You had to write special grants. Sometimes we had to ask several times before we were successful in getting whatever we needed, and we weren’t always successful.”

There is a good reason for that, said Bellini College interim Dean Sudeep Sarkar, who researched artificial intelligence at Ohio State University prior to joining USF in 1993, initially as an assistant professor of computer science and engineering. Artificial intelligence was not advancing at the same rate that it is today. Researchers were struggling to teach artificial intelligence things such as how to locate roads on maps and identify the borders of individual objects in photographs.

“We would tell friends about our interest in artificial intelligence, and they would laugh that it was useless research that would never lead to much. But we were excited about the possibilities."

Interim Dean Sudeep Sarkar

“The excitement comes from pushing the boundaries. If there’s nobody thinking you’re doing crazy stuff, you’re probably not pushing those boundaries enough,” Bowyer said.

But it was not just that USF researchers could not always get their hands on technology. Some of what they needed did not exist.

USF Provost and Executive Vice President Prasant Mohapatra

“AI has been around since the 1960s and started gaining traction in the 1980s, but it faced significant challenges,” said USF Provost and Executive Vice President Prasant Mohapatra, whose modern research includes how artificial intelligence can track online social network trends. “Some of my friends who went into that area back then couldn’t get a job and had to change areas. Can you believe that? But it was more so because technology was not ready to support their work.”

One example: In the early 1980s, there was no World Wide Web.

“Much of what we do today requires big data sets,” Hall said. “Today, we can scrape the entire internet for data. We can find a million examples for our data and fit it on a disk we can buy at the store. So, without those huge sets of data, we were mostly looking at techniques to improve performance. We then had to create the data set that the system would ingest for that purpose.”

That’s how, in 1988 and 1989, Stark and Bowyer taught an artificial intelligence system to identify a chair.

Using Computer-Aided Design software, they crafted about 250 3D models of objects that could potentially be chairs, with their emphasis on potentially being what separated their research at that time.

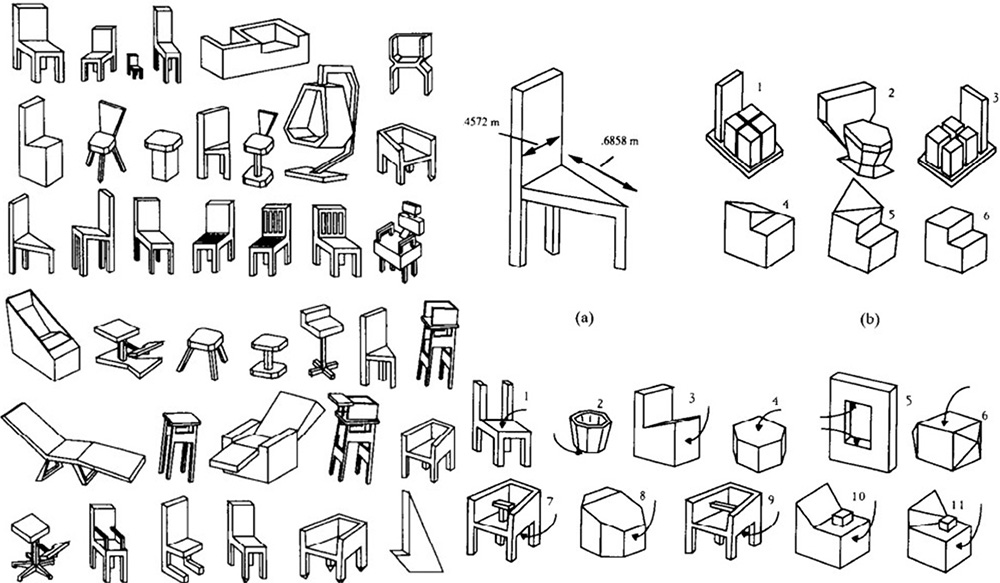

Renderings published in an academic journal that demonstrate various chairs and objects used to train AI

Other early artificial intelligence researchers typically created datasets of only the object that they wanted the system to learn to identify through memorization. Stark and Bowyer wanted to teach artificial intelligence to use logic to identify chairs among a group of similar-looking objects.

Louise Stark

“It was more common sense than anything else,” said the now-retired Stark, who, after earning her bachelor's, master's and doctoral degrees at USF in computer science and engineering, went on to become an associate dean with the University of the Pacific. “We put rules into the system to test for a sittable surface with stable support.”

The first rule was to comb through the dataset for objects with flat surfaces and put those into a group. From the next group, the system identified objects that had stable bases. But that collection might have included a trashcan, so the system then picked out the objects with back support, put those into another new group, and so on, until only chairs remained.

The research paper was published in 1992 in “IEEE Transactions on Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence."

“Then came recognition,” Bowyer said. “Nationally and internationally celebrated AI figures took notice of that research. That led to recognition of other AI research at USF. It was a breakout moment.”

In the years that followed, Stark said she watched in wonder as others improved upon her work. “One criticism of my research was that the system couldn’t identify if an object was made of paper mâché or something sturdy. So other students later added that. Others took the research in other directions by identifying things like scissors and cups.”

Bowyer is somewhat bothered when he hears people talk about how smart artificial intelligence has become. The system itself is not wise, he said, which is why it is called artificial intelligence. Rather, it only knows what it is programmed to know.

“What we are enjoying today is the result of a countless number of people over decades of time all building on the work of each other,” he said. “Some have had enormous insights. Some have had modest insights. But there isn’t one person who did it all by themselves.”

“USF’s AI community is not only taken seriously, but is at the forefront of the growing industry.” – Interim Dean Sudeep Sarkar

The same can be said about the Bellini College.

“It took a lot of resilience for USF’s early AI researchers to stick with it despite what others were saying," said Sarkar, whose recent work includes teaching artificial intelligence systems to identify someone by their gait, "and despite a lack of support."