By Paul Guzzo, University Communications and Marketing

First, there were tears.

Then, there was hope.

Now, there is inspiration.

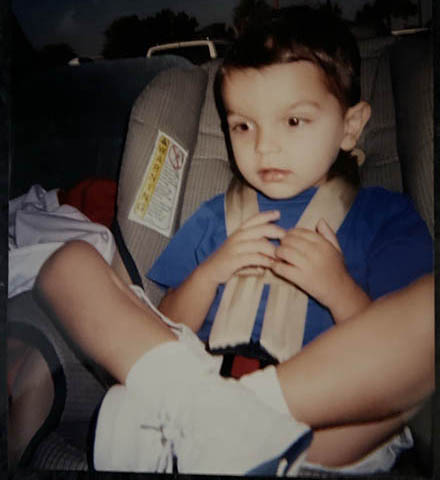

Trent Ferguson was born with optic nerve hypoplasia. [Photo courtesy of Trent Ferguson]

Trent Ferguson’s family wept when, as a baby, they learned he was blind. Ferguson was diagnosed with irreversible total blindness due to optic nerve hypoplasia.

Late one night a few months later, grandfather Dean Ferguson hoped the radio would soothe his howling grandson.

When Roy Orbison’s “Pretty Woman” came on, the baby looked in the direction of the radio.

Cries turned to coos.

“I knew then he was perfect,” the grandfather said. “I just knew he would be fine and was meant for great things. I couldn’t have known that radio would play a big role in that.”

Ferguson is now a senior at USF majoring in mass communications with a concentration in broadcast program and production.

“My dream job is to be a host or co-host of a major sports talk show on a radio network,” he said.

Ferguson has already been working toward that goal for a decade.

He got his start recording public service announcements and a podcast and then became an on-air talent for area radio stations, including serving as a color commentator for high school football games.

Ferguson initially took a break from working in radio so he could focus on his studies at USF and made his on-air return in December. From his residence hall, Ferguson produces weekday sports news segments that are broadcast at 6:30 and 7:30 a.m. on Sebring’s WWOJ 99.1.

“I'm blind, but I don't let it stop me,” said Ferguson, who writes scripts in brail and edits with software designed for the visually impaired. “I don't see it as a hindrance. I see it more as a way of life.”

None of his jobs have been pity hires. He’s not employed because he’s blind. Rather, he is a radio personality who happens to be blind.

“He has a ton of talent,” said Michael Ewing, general manager of Highlands Radio Group, which owns WWOJ 99.1. “He studies his craft. He has worked on his voice. He earns everything.”

Trent Ferguson writes a radio script in brail from his USF residence hall. [Photo by Torie Doll]

Radio beginnings

In a way, Ferguson’s on-air career began with the sound of airbrakes in his hometown of Avon Park.

When at his grandparents’ house, that noise let him know that his grandfather had returned from work driving a bucket truck for the Florida Power Corp.

“The airbrakes would pop and, starting when he was maybe 4, he’d follow the sound right to the truck,” Ferguson’s grandfather Dean said. “He’d climb in and sit in there for hours, listening to my work’s CB radio and talking to my dispatcher.”

Inside the house, his fascination with radio continued.

“He could hear a commercial jingle and then immediately mimic it on the piano,” Dean said.

He then provided his grandson with a subscription to satellite radio on which he continued to listen to Roy Orbison and similar musicians from that era.

As a little kid, Trent Ferguson spent hours on his grandfather's CB radio. [Photo courtesy of Trent Ferguson]

At around 5 or 6, wanting to hear his voice on the air, he began regularly calling into his favorite morning radio show, hosted by Gordon "Phlash" Phelps on the ‘60s on 6 channel.

“Listeners absolutely loved him,” Phelps said. “They thought a little kid who loved the ‘60s and had that great personality was the cutest thing.”

Phelps turned Ferguson into a regular part of the show.

Sometimes, he peppered Ferguson with music or elementary school trivia questions. Other times, he elicited an innocent chuckle through a cheesy joke.

- Did I ever tell you about the time I bowled a 300 and 1?” Phelps asked in one bit that he still has saved.

- “That’s not possible,” Ferguson replied.

- You ever hear about anybody who bowled a 300 and lost?” Phelps answered.

During those bits, not once did either Phelps or Ferguson mention blindness.

“No one knew,” Phelps said. “It didn’t matter.”

It mattered at school.

Teachers worried whether they were prepared to properly educate a blind student, and classmates picked on him.

“Stupid things like asking how many fingers they were holding up,” Ferguson said. “It never bothered me.”

After third grade, Ferguson’s family decided it was best for him to transfer to St. Augustine’s Florida School for the Deaf and the Blind where he lived in a residence hall, four hours from home.

“I cried almost every day at first,” he said. “I also knew it was for the best.”

It led to his pursuit of a career in sports journalism.

Trent Ferguson provides color commentary for a high school football game. [Photo courtesy of Trent Ferguson]

Becoming a radio personality

The Tampa Bay Buccaneers’ booming cannons taught Ferguson just how powerful the radio can be.

On Fridays, the Florida School for the Deaf and the Blind chartered buses to take students home and then again on Sundays to bring them back to campus. During the long rides, Ferguson listened to sports radio, especially loving the Buccaneers’ games announced by Gene Deckerhoff.

“Fire the cannons,” Ferguson screamed with his best imitation of the Tampa Bay sports radio legend’s celebratory catchphrase.

Ferguson hoped to play for the school football team as a kicker, but the physical education teacher said that would be too difficult.

“I was really bummed,” Ferguson said. “So, I thought, ‘Well, if I can’t play a sport, I will cover a sport.’”

As Ferguson’s obsession with sports grew, his other grandfather, TJ Kinyon, fed it by taking him to occasional weekend games, at which he listened to the radio broadcast while soaking in sounds and feel of the live crowd.

“If I could get tickets, he wanted to go,” Kinyon said. “He loved it.”

Trent Ferguson prepares to go to a Tampa Bay Buccaneers game. [Photo courtesy of Trent Ferguson]

Ferguson said he still gets goosebumps thinking about when his grandfather took him to a Buccaneers game for the first time to hear the canons live. That day helped him to appreciate Deckerhoff’s talent.

“Being there felt almost exactly like how he made it feel while I listened on the bus,” he said. “Through the radio, he put me in the stadium before I was ever actually in the stadium. I wanted to be able to do that for others.”

Knowing of his dream to be on the radio, in 2012, a teacher arranged a pre-game meeting between Ferguson and Enrique “Henry” Oliu, the Rays’ Spanish-radio color commentator who is also blind.

“He was a hero who became a mentor and now a dear friend,” Ferguson said. “We still talk regularly. The best advice he ever gave me was that I have to work hard for anything I want to achieve and go after it because no one is going to do the work for me.”

That advice led to Ferguson’s big break.

In 2016, while on a school field trip to Flagler Broadcasting’s radio headquarters in St. Augustine, he made sure to stand out during a class discussion with general manager David Ayres.

“He knew everything about us,” Ayres said. “I mean everything, from our formats to the height on our antenna. I was completely blown away.”

Ferguson’s self-deprecating humor also stood out. To this day, he laughingly replies with comments such as, “I will see you there.”

So, Ayres had an idea for the go-getter. He made Ferguson the voice of public service announcements advocating against texting while driving -- as in, it’s so dangerous, it even scares the blind.

Ayres next connected Ferguson with Flagler Broadcasting radio personality Rich Carroll. The two launched the tongue-in-cheek podcast Outta Sight Sports – later becoming a regular part of Flagler Broadcasting’s WNZF’s Saturday morning lineup. That led to Ferguson being promoted to weekday morning sports anchor.

“I was clear that if he could not edit, I could not keep him,” Ayres said. “I wasn’t just giving him a job. He had to earn it. He promised it would not be an issue, and it wasn’t. There is nothing he cannot do.”

That included working as Flagler Broadcasting’s radio color commentator for high school football games. He couldn’t analyze the play, so he brought other things to the broadcast.

“I prepared by talking to the coaches, studying old stories and statistics and reading through the athletes’ social media pages,” Ferguson said. “I wanted to learn personal stories and add those tidbits to the game.”

After earning an associate degree from South Florida State College, he considered several schools for his bachelor’s degree but chose USF partly so he could be in the same radio market as his favorite sports teams.

“The scene is terrific with the Bucs, the Lightning, the Rays, the Rowdies and the Sun,” he said. “I hope to land in the Tampa Bay radio market someday.”

But Ferguson was also drawn to USF because he trusted the professors would work with his blindness while not giving him a free pass.

“I don’t want anything handed to me,” he said.

Trent Ferguson is majoring in mass communications with a concentration in broadcast program and production. [Photo by Torie Doll]

On to USF

Senior instructor Wayne Garcia’s Media and Society class had 300 students in a large lecture hall, yet Ferguson stood out on the first day.

“Heads turned as he walked in with a cane,” Garcia said.

As the semester progressed, Ferguson continued to stand out, but on his terms.

“He was always the first to start a dialogue when I’d ask the class a question,” Garcia said. “He never shied away from the spotlight.”

During one class, they were planning a field trip and debating the best way to meet up. Ferguson offered to drive everyone.

Trent Ferguson provides color commentary for a high school football game. [Photo courtesy of Trent Ferguson]

“That’s Trent. He was obviously joking – maybe,” Garcia said with a laugh. “He is so confident that he can do anything. He doesn’t believe in obstacles. He’s probably taught me more than I have taught him. I’ve always said that anything is possible with hard work, but Trent proves that.”

Ferguson’s degree requires video production classes. In lieu of creating visual projects for Electronic Field Production, instructor Ryan Watson allowed Ferguson to produce audio ones. He produced a car chase story in the style of old radio serials. And for a documentary, he created one about how to navigate the campus while blind. It used only oral and written narration, interviews and sound effects while the screen remained black to symbolize blindness.

“He doesn’t make excuses,” Watson said. “He didn’t tell me that he couldn’t do the projects and ask for a way out. Instead, he found a way to participate and be the best version of himself. You can’t help but to love his work ethic.”

But there was no workaround for the TV Direction and Production class. Ferguson had to direct a scene. So, he got creative. He produced a name-that-tune game show, researched camera angles and learned what ones similar programs typically use for specific scenes and moments, and conveyed those to the crew in real-time.

“I was calling the shots,” Ferguson said.

He always has, and that, and not blindness, is his definitive quality, Grandfather Ferguson said. “He adjusts to everything. He always finds a way to do things. That’s what makes him perfect. You don’t have to be perfect to be perfect.”