A PhD student in the School of Geosciences, John Henson, attained the prestigious Chateaubriand Fellowship in the Spring of 2022. This accolade gave him a six-month study opportunity at the University of Montpellier in France, spanning from March to August of 2023.

Offered by the Embassy of France to the United States (U.S.), the Chateaubriand Fellowship is a grant given to exceptional PhD students, allowing them to complete part of their doctoral research abroad and build relations between the U.S. and France. The duration of the fellowship ranges between four to nine months and fellows are selected based on merit.

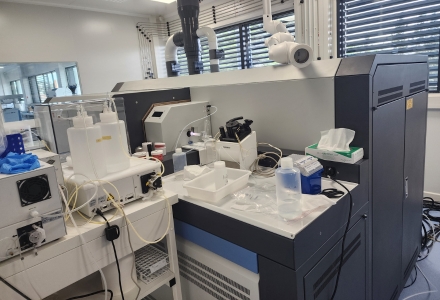

The ICP multi-collector machine. (Photo courtesy of John Henson)

“Dr. Auérlie Germa is the one who recommended the fellowship to me. I wrote a proposal about my research and how it would help create a collaboration between U.S. and French institutions. During the last round of interviews, they offered me $7,000 to go to France for up to six months. I decided to challenge myself and see if this, ‘good old boy from the swamp’ could make it to France,” Henson said.

In addition to pursuing his PhD, Henson also serves as a research assistant in the Plasma Instrument Laboratory. In the lab, he works with an inductive couple plasma (ICP) machine, specifically a mass spectrometer. This machine measures masses of certain elements allowing them to be easily identified in samples of rocks.

Through this work in the lab, Henson and his advisors, Dr. Jeff Ryan, Dr. Zachary Atlas, and Dr. Auérlie Germa, study the chemical characteristics and evolution of magmas that erupted in the Eastern Caribbean. This became the research that Henson took overseas to France, as many of the Caribbean Islands are still French territories. But this topic of research came about in quite an unlikely way.

In the late 60s and early 70s, Dr. Fredrick Nagel, a researcher at the University of Miami, roamed the Caribbean Islands, collecting hundreds of rock samples from regions such as Cuba, the Dominican Republic, Venezuela, Martinique, and more.

One day while cleaning the basement of the chemistry building, Henson came across a box with the names of islands he had never heard of before. To his surprise, this box turned out to be Nagel’s rock samples along with his detailed research notes.

“I was actually down in the basement cleaning up things, and I came across a box with the names of islands that I've never heard of before. I found Dr. Nagel’s journals documenting further islands that are down in the basement that need to be analyzed as well. The rock samples from these islands are extremely rare because nobody can go to them anymore. When Dr. Nagel took these samples, these islands were just goat farms and bird sanctuaries, now they're military bases occupied by other countries,” he said.

This discovery was made one week before Henson’s departure to France. Given the uniqueness of this find, he decided to abandon his initial research proposal and shift his focus toward studying these samples. Armed with the samples, he embarked on his journey to France.

“I was only able to carry 23 samples with me because of weight limitations on suitcases. When I originally wrote the proposal, it was based on certain aspects of research that were unfinished and other issues arose from the methodology. It was fortunate that I did find these samples because I met one of the researchers in France who had previously worked with the researchers referenced in my original proposal, and he stated that the original researchers never had much confidence in that particular isotopic system to begin with,” Henson said.

To unravel the mysteries of the rock samples, Henson and the researchers at the University of Montpellier used research methods known as major and trace element analysis and isotope analysis.

“To understand how this works, a major analysis is when we look at the major elements such as silica, aluminum, iron, sodium, potassium, titanium, phosphorus, etc., that are measurable by a higher weight percentage in a sample. So, the trace element analysis is similar, but the elements are not in weight percent, and it can be used to detect smaller metals like strontium, neodymium, molybdenum, vanadium, etc.,” Henson explained. “Now, the isotope analysis is used to determine magma source. Isotopes will tell us a little bit more, like if the sample comes from the Earth’s mantle. We also look at the uranium to lead isotope ratio, which is primary use for aging a sample. The island samples that I analyzed are between 45 million years all the way up to 100 million years old, so I have a massive age range to look at.”

John Henson playing Pétanque with his host family abroad. (Photo courtesy of John Henson)

Since the Caribbean is only about 25 million years old, this added a different perspective to what is known about the region’s tectonic plate system. The proposed theory suggests that a large land mass called GAARlandia (GAAR stands for Greater Antilles and Aves Ridge) existed in the Caribbean Sea millions of years ago. Henson hypothesizes that some of the islands from which the samples were gathered, are the remnants of that once existing land mass.

A few of these islands are most likely elevated fragments from the ocean floor as a result of a transform boundary between the Caribbean and South American plates. Transform boundaries are locations where plates slide horizontally past each other, the most notable example being the San Andreas fault line.

“When it comes to tectonic models, we have to keep in mind that these models change a lot, but the overall idea is the same. Our planet is changing constantly and the planet that our ancestors saw was vastly different than the planet we see today. As this planet is evolving, we can maybe help ourselves discover what future configuration the Earth is going to make in the next million years. This kind of research helps us understand how our Earth is constantly changing, constantly evolving,” Henson said.

During his time in France, Henson not only conducted research but also immersed himself in the town of Montpellier, engaging in local activities. Some highlights included exploring Roman aqueducts, touring countryside vineyards, and visiting some of the world's oldest cave paintings at the Grotte Chavet Cave. Henson also fondly remembers a game his host family taught him called Pétanque.

“In Pétanque, you have two have balls made out of steel, and the goal is to use these balls to hit a smaller ball. Whoever gets closest to the smaller ball without knocking it out of the ring wins. It can get tricky because other players will come behind you and knock your balls away,” Henson explained. “One of the people that I played with was so accurate with the ball I gave him the nickname, ‘The Hitman.’ Every time I would get really close to winning, he would come behind me and throw a ball that would knock mine right out of play.”

As he looked back on the Chateaubriand Fellowship, Henson acknowledged its positive impact on the relationship between USF and the University of Montpellier, even leaving behind samples to continue the research collaboration across institutions.

“The equipment at the University of Montpellier was amazing. An added benefit was that I was in a national research lab, with the opportunity to speak with a variety of different researchers. I actually left some samples for other researchers to use for future collaborative efforts. What their team is doing is that they are looking more at the chemical side and isotopic systems, not so much the geologic setting. One of the particular researcher's goal is to analyze specific barium isotopes in subduction settings. He is actually filling out a European research grant to look at the barium isotopic systems further,” Henson said.

Encouraging fellow graduate students at USF, Henson advocates for international work. He emphasizes how this opportunity has opened doors for research opportunities and offered him new perspectives from veteran researchers.

A trail of Titanosaurus footprints that John Henson visited near the Montpellier region in France. (Photo courtesy of John Henson)

“For the graduate students here at USF, one of the things that I've noticed is that we all have some form of anxiety when it comes to our research. It seems like we're always unsure about what we're actually doing, but through this experience I learned that it’s okay. One of the researchers in France has been in geosciences for 50 years. While attending his retirement party he told me, ‘Yeah, I don't know what I've been doing for 50 years, but hey, I made a career out of it.’ They may have an idea, but until we actually have the results, that idea is just a good guess,” Henson said. “If you're doing research here at USF and you have an advisor that has international contacts, see if that university or that country where they connected has some kind of collaborative fellowship. These kinds of opportunities can further expand your knowledge on whatever your subject might be.”

To learn more about the programs and research opportunities visit the website for the School of Geosciences.